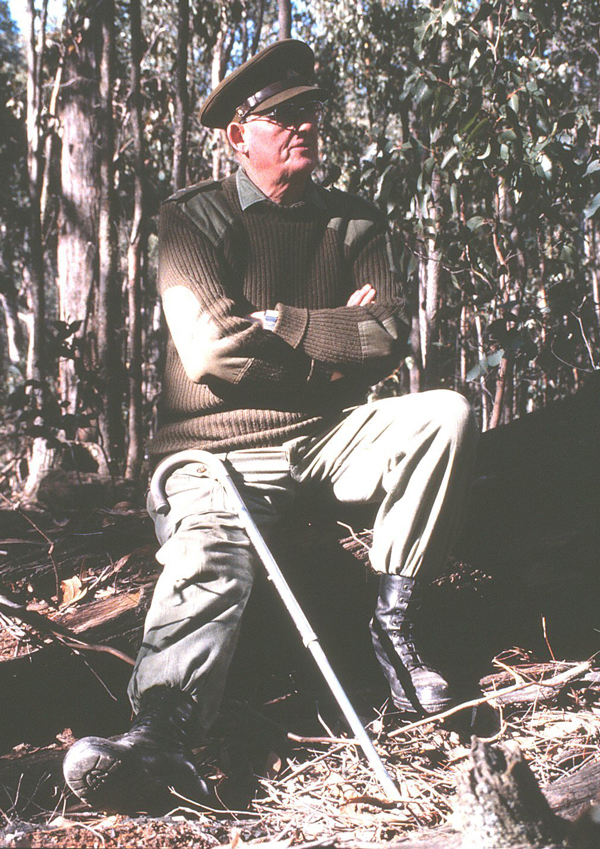

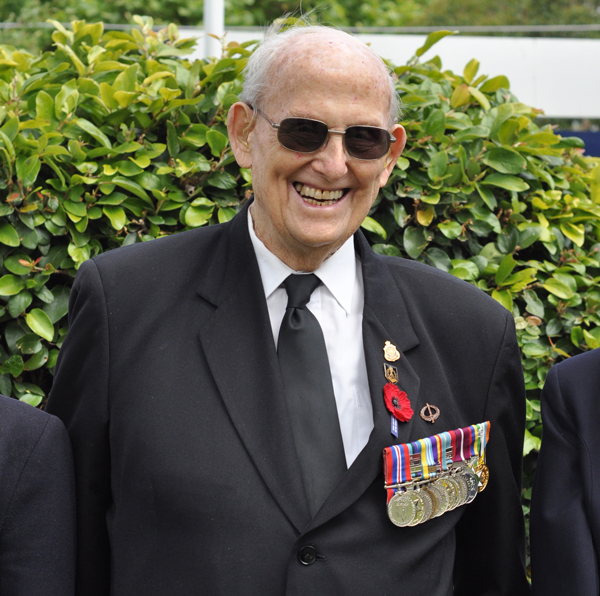

FRANCIS REGINALD "SMUDGER" SMITH (1927 - 2015)

All of us, family and friends, will carry with us for the rest of our lives various pieces of the life jig-saw that was Francis Reginald Smith.

Somewhere out there, whether on a distant battlefield, running the library charging desk at Mentone Grammar, organizing, refurbishing and readying stores for an Annual Camp, or simply sharing a beer and a yarn with one of his many mates; wherever it was there will be remembrance, affection and love for the man we knew best as “Smudger”.

One thing Frank ‘Smudger” Smith was not was an enigma. Once you met Smudger you were “Mate”, no further questions asked – though you were expected to live up to his standards – of course. And as you worked alongside him you found a man of extraordinary generosity, great good humour and pride. But the pride that shone forth in him was not that malignant kind that we see in self-regarding people who affect eminence and are full of self-importance. Smudger’s sense of pride consisted in seeing a job well done, completed as painstakingly as possible. The difference between these two senses of pride was well illustrated when, on one occasion, Smudger, in warning someone not to get above themselves, was heard to say: ”Just remember that you’re and old baggy-arse like me”.

Perhaps service in the army gave Smudger a sense stability and achievement that he did not encounter in the civilian world. In reflecting back upon his working life, which he did with complete satisfaction, he said “I always wanted to be soldier and that is what I did”. There was one brief interlude ‘on civvy street’, but this period seems only to have confirmed his vocation to the profession of arms.

Smudger Smith was an Englishman by birth, though, he has been quick to point out that he became an Australian citizen – “neutralized”, as he put it – whilst serving in Malaya in 1957. His family moved from Medway, Kent where he was born in 1927 and, after a brief time in the docklands of Tilbury, settled in Croydon, Surrey. In about 1940 Smudger made a momentous decision in joining a local Cadet Detachment fostered by the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. After some further training this led young Rifleman Smith to a stint of service patrolling the Yugoslav-Italian border at end of the Second World War.

After returning to England to a less than satisfying civilian job, he noticed that Australia was recruiting ex-British army personnel for service in Korea. He readily chose to re-enlist in 1950 and after yet more training was off to Korea. He arrived to join 3 RAR just after the historic battle of Kapyong. His remembrance of his arrival in the battle area at 10 o’clock at night was stark and filled with apprehension: he was thrown a shovel and told to “start digging”. There followed a second tour of duty in Korea with 2 RAR and then home, this time to Australia.

In 1948 the ‘Emergency’ had been declared in Malaya. Smudger spent four years of active service in this theatre as a mortar sergeant, but was involved most of the time in vigorous and exhausting patrol warfare close to the Thai-Malay border.

It was not until 1964 that Smudger was posted as a Warrant Officer Instructor to 3 Cadet Brigade in Victoria. He worked with many school units. There grew within him all the while a deepening appreciation of the value to young Australians of some form of cadet training. He put it this way: “The cadet scheme fosters discipline, instils a sense of duty and promotes teamwork, all important lessons “.

After service in Vietnam, Smudger was once again back with cadets , still a Regular Army Warrant Officer. In 1974 he decided to retire from the army. “To be in the infantry you have to be a young man” he remarked “and I had had my time”.

Smudger was again forced to confront civilian employment, this time as a security officer with H.J. Heinz Co. This he did not enjoy, the irregular rostered hours in particular. Bruce Lobb, a friend and colleague from army days , who was Mentone Grammar’s School Marshal at this time, was aware of Smudger’s situation and of the School’s need for a man of his background to act as Quartermaster in the Cadet Unit and to assist with the routines of the Library. And so it was that Smudger joined the staff of Mentone Grammar early in 1978. At a time of life when many old soldiers are ready to take their ease, Smudger was eager to embark on a fresh chapter in his own career.

This led, amongst other things, to a pretty rich folklore surrounding Smudger. First to have some innocent fun was the Headmaster of the time, Keith Jones, who detected a bit of double dipping on the part of a platoon of cadets being issued with clothing. These fellows were rejoining the end of queue in an endless “conveyor belt”of issuing and re-issuing. Some time later – and whether the two were in any way connected is uncertain – Smudger had a dream involving himself and the Headmaster. In this dream he was a passenger in a car being driven by the Headmaster, who drove the car to the edge of a precipice such that it was balanced there and rocking to and fro. According to Smudger, Keith Jones remarked that he often did this to keep himself amused. I remember recounting this dream to the Headmaster whose comment was “That’s me, always on the edge of a precipice”. Smudger drew considerable satisfaction from imitating the Head’s remark.

On another occasion, Smudger was pursuing a student for an outstanding library fine of 40 cents. This game of cat and mouse continued until the errant student was finally confronted. Then perhaps the master stroke: the student pulled out a $100 note. Unperturbed, Smudger reached to the library’s considerable stock of 20 cent coins and proceeded to count them out one by one. The student seeing immediately that this transaction might well lead to the loss of his trousers speedily found the 40 cents.

Cadet camps were, of course, Smudger’s forte, the time when his endless years of regular army training would surely outclass us all. Smudger took particular pleasure in instructing the young raw recruits of C Company in matters field hygiene, including the use of latrines. These were in those days the pan canopy type, under which a substantial hole had been dug. Smudger would have the recruits seated in front of the pristine demonstration latrine. What the young recruits did not know was that one of the smallest of his Q Store boys had earlier on inserted himself into the hole and pulled the latrine canopy over his head. Smudger’s lecture proceeded apace, until on a given signal the canopy lid began to rise by infinitesimally small degrees until full disclosure was achieved.

On another occasion, the Headmaster, then Neville Clark, MC, visited the camp. He was observing cadets attempting to light a HQ fire with minimal materials. The Head remarked that, despite the obvious difficulty the cadets were having with this task, he was extremely pleased to see them doing the job properly. Smudger, who had not been party to the Head’s arrival and remarks, had decided that he could tolerate this difficulty no longer, came round the side of the tent with a drum of kerosene and brought about a conflagration – much to the cadet’s relief, though somewhat nullifying the Headmaster’s wishes.

We, of course, became accustomed to that special dialect spoken only by Smudger and so far without an established dictionary or lexicon. In this special jargon a kitchen spatula became a ‘spattle’ and the act of daubing graffiti on library carrels was expressed in a new verb ”to graffique’, as in “some higgorant so-and-so has been graffiquing on the carrels again.

Smudger usually had the last word, as when two gentleman from the Sport Staff decided to try and get a rise out of him after a Cadet Camp. “Been on your holidays again have you, Smudger?” The effect was immediate and something like: “I’ll teach you two useless layabouts something about holidays” and a fairly well aimed and highly destructive barrage of words followed.

Smudger, what will we do without your humour, generosity and straightforward humanity? With your passing we seemingly lose a part of ourselves. How can we assess your significance in the lives of so many others? Perhaps, so you told me once, the disarmingly simple criterion you applied in appraising officers and NCOs from your own experience says more about you than anything else: “He was good; he looked after his diggers”.

Read at the memorial service for Francis Reginald Smith.